Confidence is indispensable for leadership. It fuels ambition, enables decisive action, and inspires teams to overcome challenges.

Yet, significant success, particularly when concentrated in a specific domain, can paradoxically breed a dangerous form of overconfidence:

PODIUM HUBRIS.

This phenomenon describes the tendency for highly successful individuals to develop an inflated belief that their mastery in one area translates directly to extraordinary competence in any new endeavour they pursue.

Drawing its name from the “podium effect”—where top finishers receive disproportionately high recognition—this type of hubris emerges when leaders assume their proven ‘winning formula’ is universally applicable, often leading to costly strategic errors.

This article analyses the roots and manifestations of podium hubris, examines its detrimental impact through case studies, and proposes strategies for leaders and organisations to mitigate this critical risk.

THE COGNITIVE AND SOCIAL DRIVERS OF PODIUM HUBRIS

The susceptibility to podium hubris stems from a confluence of well-documented cognitive biases and reinforcing social dynamics:

Cognitive Biases: Success can trigger cognitive distortions such as the Dunning-Kruger effect, where limited competence results in overestimating one’s ability or the Halo effect, where positive impressions in a specific domain cast an unwarranted glow of perceived competence across unrelated areas. Leaders may mistakenly attribute domain-specific success solely to innate talent or a universal method rather than acknowledging the role of context-specific expertise and situational factors.

Social Reinforcement: Society and organisations often lionise successful leaders, showering them with accolades, resources, and deference. This external validation can inflate egos and create echo chambers, insulating leaders from constructive criticism. Surrounded by advisors reluctant to challenge their judgement, leaders may increasingly believe their intuition is infallible, reinforcing the conviction that their past success guarantees future triumphs in any field.

Podium hubris, therefore, is not merely a personal failing but can become a structural vulnerability within organisations, creating fertile ground for strategic overreach into unfamiliar markets, technologies, or management challenges.

CASE STUDIES IN STRATEGIC OVERREACH

The detrimental effects of podium hubris are evident across various sectors when successful individuals step outside their core areas of expertise:

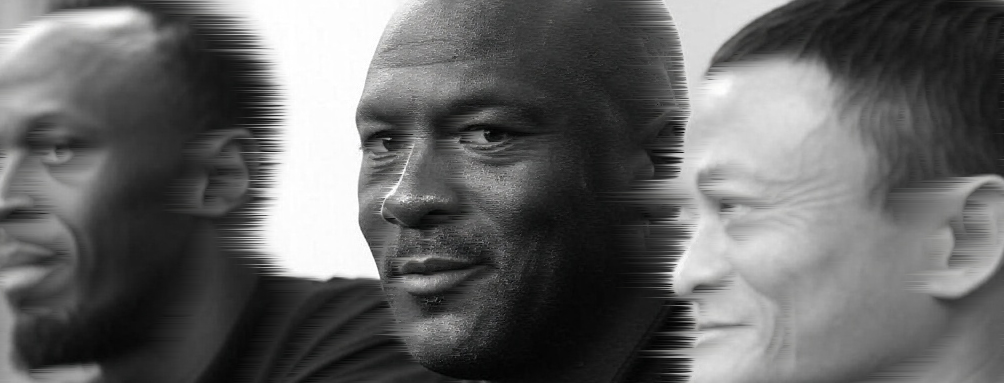

Michael Jordan – Athletic Superstar Across Sports

Widely regarded as basketball’s greatest player, Jordan’s dominance was built on unparalleled skill and competitive drive. However, his mid-career pivot to professional baseball showed the limits of transferable athletic talent. Despite intense dedication, the specific skill set required for baseball differed fundamentally from basketball. His struggles in the minor leagues highlighted that even peak physical conditioning and a champion’s mindset cannot substitute for domain-specific expertise developed over the years. His eventual return and continued success in basketball further emphasised the domain-specific nature of elite performance.

Usain Bolt – From Sprinting Legend to Music Misfire

Usain Bolt, the Jamaican sprinter widely regarded as the greatest of all time, dominated track and field with eight Olympic gold medals and world records in the 100m and 200m. His global fame and charismatic persona earned him a podium spot in athletics. Post-retirement in 2017, Bolt ventured into music production and DJing, believing his celebrity and energy could make him a successful reggae and dancehall artist.

Bolt’s music career flopped commercially and critically, including his 2021 album Country Yutes. Tracks like “Living the Dream” failed to resonate, lacking the polish and authenticity expected in Jamaica’s competitive music scene. Bolt’s hubris was in assuming his athletic fame and casual interest in music could translate into mastery of a creative field requiring years of craft and cultural nuance. His music ventures quietly faded, underscoring the gap between sprinting stardom and musical expertise.

Jack Ma – From E-Commerce Giant to Entertainment Flop

Jack Ma, the Chinese founder of Alibaba, revolutionized e-commerce, making his company a global powerhouse rivalling Amazon. His podium status as a tech visionary and charismatic leader led him to believe he could dominate the entertainment industry. In 2015, Alibaba Pictures, under Ma’s guidance, invested heavily in film production and distribution, with Ma personally promoting projects like the 2017 martial arts film Gong Shou Dao, in which he starred.

Alibaba Pictures struggled with box-office flops and financial losses, as Ma’s vision of blending tech and entertainment underestimated filmmaking’s creative and cultural complexities. Gong Shou Dao was panned as a vanity project, and other films failed to resonate with audiences. Ma’s hubris lay in assuming his e-commerce success and personal brand could translate into cinematic triumphs, ignoring the specialised expertise required in storytelling and audience engagement.

THE STRATEGIC COSTS OF PODIUM HUBRIS

The consequences of leaders succumbing to podium hubris extend far beyond personal failure; they pose significant organisational risks:

Strategic Missteps – Overconfidence leads to poorly conceived market entries, acquisitions, or product launches in areas where the organisation lacks core competencies.

Financial Losses – Failed ventures drain resources, destroy shareholder value, and jeopardise the financial health of the core business.

Reputational Damage – High-profile failures erode trust among customers, investors, employees, and the public, damaging both the leader’s and the organisation’s brand.

Organisational Dysfunction – Hubristic leadership can stifle dissent, marginalise expert opinions, demotivate employees, and undermine collaborative culture.

CULTIVATING ORGANISATIONAL DEFENCES AGAINST HUBRIS

Mitigating the risks of podium hubris requires conscious effort from both leaders and the organisations they helm. This involves fostering a culture and implementing systems that promote humility and rigorous decision-making:

FOR LEADERS

> Practise Critical Self-Reflection: Regularly assess the true drivers of past successes and honestly evaluate competency gaps when considering new ventures.

> Actively Seek Diverse and Challenging Feedback: Cultivate a network of trusted advisors (inside and outside the organisation) willing and empowered to provide candid criticism.

> Explicitly Respect Domain Expertise: Acknowledge the value of specialised knowledge and defer to experts in fields outside one’s own core competence.

FOR ORGANISATIONS

> Implement Robust Governance and Feedback Mechanisms: Ensure board oversight, independent reviews for major strategic initiatives, and formal processes (like 360-degree feedback) that provide unfiltered input on leadership behaviour.

> Foster a Culture of Intellectual Humility: Encourage open debate, make it psychologically safe to challenge prevailing ideas (even the leader’s), and normalise acknowledging uncertainty.

> Diversify Decision-Making Inputs: Involve cross-functional teams and external experts in strategic assessments, particularly when exploring unfamiliar territory.

> Broaden Recognition Criteria: Celebrate collaborative successes and operational excellence, not just singular “heroic” achievements, to temper winner-takes-all dynamics.

BALANCING CONFIDENCE WITH HUMILITY

Podium hubris represents a significant, if predictable, hazard accompanying exceptional success. While confidence is essential for leadership, it becomes counterproductive when it detaches from domain-specific competence and fosters an illusion of universal mastery. Jordan, Bolt, and Ma’s examples are potent reminders that past performance in one arena is no guarantee of success in another.

For sustained high performance and strategic resilience, leaders and organisations must proactively cultivate self-awareness, institutionalise checks against overconfidence, and foster a profound respect for the distinct challenges and expertise required by each new domain they seek to conquer.

In today’s complex global landscape, the capacity for humility may be the most critical leadership trait of all.